10th May 2024

Introduction

Post-pandemic reopening of international borders and regaining of travellers’ confidence in cross-border travels created a surge in international travel and observed a ripple effect in the tourism industry. The recent magnificent inauguration of Ram Mandir in Ayodhya with a projection of Ayodhya as a global spiritual hub enhances India’s prospect as a global spiritual destination, probably not lesser than Vatican City. The government of India should encourage researchers to explore the topics of spiritual destinations and to relook into the major elements comprising the destination competitiveness and critically analyze the possibility of India gaining a higher position in the Spirituality index. India’s religion and spiritual market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 10% in 2024-32, with a market size of USD 58.56 billion in 2023 (Expert Marketing Research).

Spirituality and Spiritual Tourism

Spirituality means connecting with the self and it consists of a set of ideas related to self, wholeness, holism, interconnectedness and a quest for peacefulness and tolerance. It might or might not have an affiliation with religion (Smith et al., 2010). Spirituality includes feelings and belief in the purpose and meaning of life and connection with others. Leisure and spirituality are often connected by the tourism sector (Doohan, 1990). Balance of body-mind and spirit and overall well-being relate to spiritual tourism and it is often promoted as an extraordinary experience which is different from the way we feel at home. The search for fulfilment and meaning of life is one primary motive for spiritual tourism. The modern transformation of religion into spirituality, harmony between individual and environment and the overlap between religious practices, meditation, yoga, and wellness attracted enthusiasts to the prominent global spiritual destinations. Spiritual tourism is projected as a subset of religious tourism and pilgrimage and the spiritual tourists visit a place to gain spiritualism, the inner meaning of life without overt religious compulsions. They love to be called travellers, seekers, festival attendants, adventurers, experiential tourists or even classical pilgrims or devotees. The seven dimensions of spiritual tourism as identified by Halim et al. (2021) are purpose or a quest for life, consciousness, transcendence, spiritual resources, self-determination, reflection and soul purification, and spiritual coping with hindrances

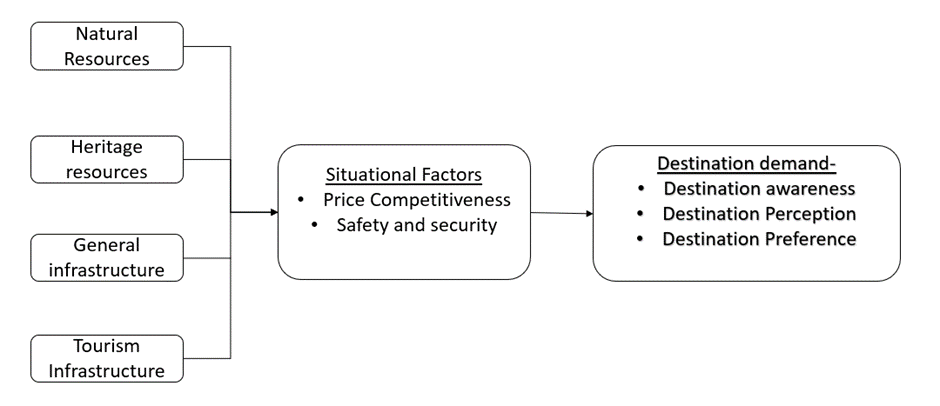

Destination Competitiveness Destination competitiveness is the ability of a destination to deliver goods and services to the tourists better than other destinations that encompass price differentials (Dwyer et al., 2000), exchange rates, productivity levels of various components, qualitative factors and attractiveness of the destination. Hassan (2000) has defined destination competitiveness as the ability of the destination to create and integrate value-added products and the ability to sustain its market position among its competitors. It is measured by several factors like a number of visitors, market share, tourist expenditure, employment in the tourism sector, value added by the tourist industry, and qualitative factors like culture, heritage, tourists’ experience etc.

Measurement of India’s global competitiveness as a spiritual destination competitiveness

Model to measure India’s spiritual-destination competitiveness based on the model of Dwyer & Kim (2013)

Attractiveness of India as a spiritual tourism destination

India, a 5000-year-old nation with diverse cultural and religious practices the birthplace of Lord Buddha, Mahavir Jain, Ramakrishna, and Vivekananda is famous as a tourist destination. India with its rich history, culture, heritage buildings, sacred temples, gorgeous churches, opulent mosques, beautiful monasteries and marvellous gurudwaras has so much to offer to all kinds of tourists from every nation, religion, or race. The country is known for its religious secularism, integration, and peace. Moreover, the Government of India’s several promotional programs like “Incredible India”, and “Atithi Devo Bhavah”, along with different states’ initiatives and public-private partnerships are acting together toward planning, development and promotion of spiritual tourism in India. According to Norman (2012), spiritual tourism can be classified into five broad categories based on the traveller’s motivations,

1. Spiritual Tourism as Healing- Mental, physical, and psychological well-being are associated with it and tourists look for places like Yoga centres, retreats and Ashrams.

2. Travellers seek answers to the purpose or meaning of life, quest for knowledge and follow gurus, and mentors, attend seminars, religious practices, meditation, lectures, and this tourism is categorized as a spiritual tourism quest.

3. Spiritual tourism is categorized as an Experiment where travellers venture into experiments and prefer naturally attractive, adventurous, aesthetically beautiful places with spiritual activities and experiments.

4. Spiritual tourism is a retreat where tourists look for a break from routine life and anti-stress therapy, mental renewal, Spas and eco-tourism hubs.

5. Spiritual destination as a collective where many people gather for a common spiritual event or religious celebrations.

India with its gorgeous mountains, soothing beaches, and cultural diversity has several places for spiritual awakening, starting from Yoga therapy at Haridwar in the North, to Kerala in the South, meditation centre at Art of Living in Bangalore to Isha Foundation in Coimbatore or Auroville at Pondicherry. Kasi Temple in Varanasi, Jagannath Temple at Puri, Kalighat at Kolkata, Kedarnath, Badrinath and the recent addition of Ayodhya Ram temple are marvellous pilgrimage and old shrines for spiritual and religious devotees. Kumbh Mela at Prayag, Rathayatra at Puri or Durgotsav at Kolkata are well known for collective spiritual experiences.

Conclusions

Make my trip, the travel portal reported a remarkable 1806% increase in searches for Ram Mandir after the inauguration of Ram temple in Ayodhya on 30th December 2023. Demand for India as a Spiritual hub has been observed globally, especially from the USA, Canada, Gulf Countries, Australia, and South Asian countries. The number of global tourists whether for religious purposes or for spiritual connections increased substantially and contributed towards achieving better scores and ranking India at a higher position in global competitiveness as a spiritual destination. Improvement of government efficiency, business efficiency, infrastructure, economic performance, and public-private enterprises should work together to make India the brightest spot in the global tourism destination and India should have a very strong positioning as a country to visit for a spiritual awakening.

Disclaimer- This caselet can be used in Marketing Management and Business Research Methods in PGDM

Questions

1. Formulate Hypotheses to establish the Model to measure India’s spiritual-destination

competitiveness

2. Prepare a research plan or framework based on the above discussion.

3. Give an example of each classification on Spiritual Destination from India and outline two promotional strategies.

References

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Rao, P. (2000). The price competitiveness of travel and tourism:

A comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management, 21(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/

10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00081-3.

Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators.

Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/

13683500308667962.

Halim Mutia Sobihah Abd; Ekrem Tatoglu; Shamsiah Banu Mohamad Hanefar, (2021), “A Review of Spiritual Tourism: A Conceptual Model for Future Research”, Tourism and hospitality management 27(1)

Hassan, S. S. (2000). Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 239–245. https://doi.

org/10.1177/004728750003800305

Norman A (2012) The Varieties of the Spiritual Tourist Experience. Literature & Aesthetics 22 (1):20-37.

Smith, S. (1994) The tourist product. Annals of Tourism Research 21 (3), 582–95.